Forward March map

What the eye does not see….

I know that for many wargamers that the real pleasure comes from seeing beautifully painted figures on a tabletop. Yet for me, the usual bare, green blanket with a few ‘terrain items’ plonked on it, often following some archane set of rules to produce a ‘balanced battlefield’ is the antithesis of what a wargaming tabletop should look like. For one thing, such tabletops lack any idea of scale, the figures are usually over-sized, arranged in groups of 24 representing 500 to 600 soldiers and if you are lucky the buildings relate to the size of the figures.

However, most geographic features will not be to scale, as they will adhere to the ground scale, so hills, woods and rivers will be completely the wrong size relative to the figures, and of course the houses. Trees will not be to scale with the figures because they would be too large and they are not to scale with the ground scale, because they would be too small. The woods area is sized to the ground scale but tends to be on the small size as this impedes the flow of the action. So on most tabletops a wood actually represents nothing of reality at all, except the concept of being a wood with trees in it.

The conflict of scales between the models, the troops, the geographic features and the ground scale all produce a muddle, so the average wargamer has no real concept of scale at all. We have a model scale 25mm, imposed on a figure scale of 1 model = 50 men, connected with a ground scale of 1; 1,500, linked to a turn of 15 minutes, so that the 25mm soldiers march a distance of 6” in 15 minutes which represents 1,000 paces. In the midst of this cacophany of scales and measurements, what is the average size of a wood in the early 19th century? An awful lot larger than most wargamers think. Some rules take this situation to the final degree and make the terrain completely abstract, as in the Portable Wargame or H.G. Well’s Little Wars. There is nothing wrong in any of this and especially ‘abstract’ games fill a valuable niche.

A reconstruction of a Prussian military wargame (Kriegsspiel), based on a ruleset developed by Georg Heinrich Rudolf Johann von Reiswitz in 1824. Matthew Kirschenbaum https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kriegsspiel_1824.jpg

But let’s not forget that the first modern wargame, the Kreigsspiel of 1824 authored by v. Reisswitz was played on maps with accurately scaled terrain, troops that matched it in scale, together with movement and rules, all in harmony at a scale of 1;2,373 or later at 1;8,000. Now modern versions of Kreigsspiel do exist, in fact I own a copy of Bill Leeson’s reprint myself and have a series of maps and troops to match. There are several groups devoted to the game such as the Kreigsspiel Society and the International Kreigsspiel Society. If you are interested have a look at Bill Leeson’s website on the 1824 Kreigsspiel game and explore the fascinating birth of our hobby.

Pieter van Snayers - Siege of Presnitz 1641

Yet Kreigsspiel for all its accuracy is essentially 2D and representational. We can contrast it with the paintings of Pieter van Snayers and Sebastian Vrancx as 3D presentations of reality which show troops and battles within a stylised terrain. These types of paintings were used by Sidney Roundwood to create his 2mm Lutzen game and later went on to inspire the English Civil War Siege of Portsmouth Campaign which was run at Partizan in 2018.

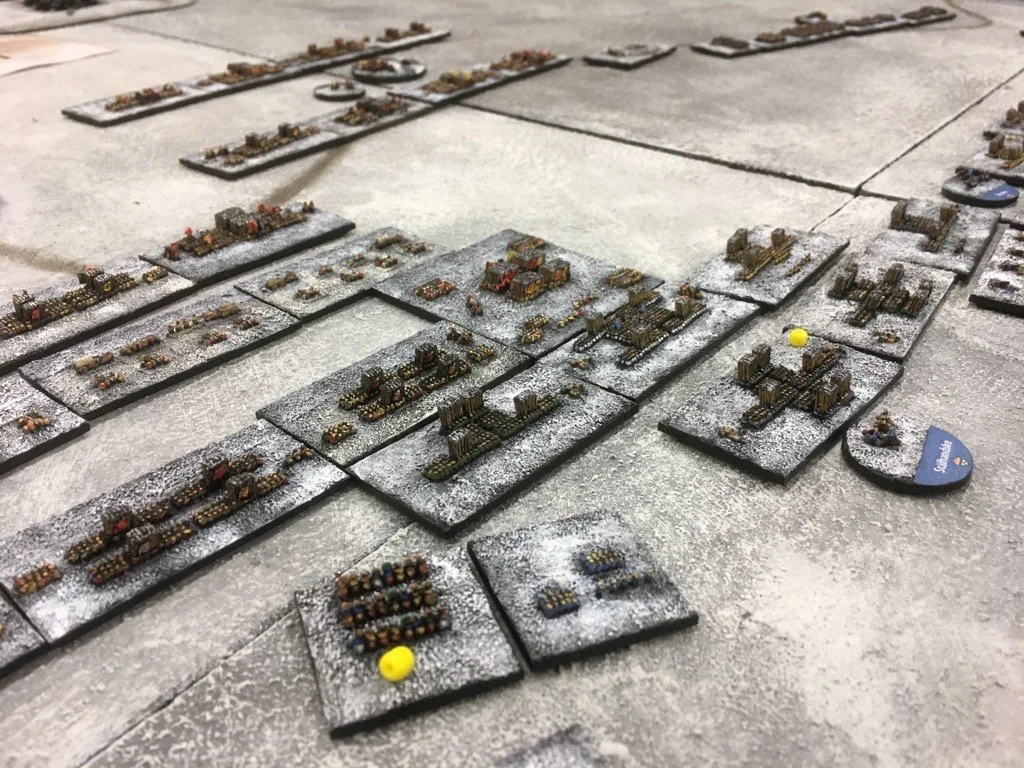

Sidney Roundwood’s 2mm Lutzen game

Both of these examples draw on Snayers paintings as an inspiration to set real life formations of troops within a ‘landscape’ as depicted by an artist and to combine the two together so that size and scale are maintained and complement each other. It’s a step away from Kreigsspiel, yet retains its accuracy and adds in the third dimension of height. What is lost in in the traditional ‘Little Wars’ type of game is the concept of terrain as Landscape, the idea that we have a complex geographic layout that has considerable significance to both the troops, warfare and the outcome of the battle. The size of geographic features matter and have a bearing on the battle. A wood is not 500 paces square and plonked down in the middle of an open plain. It is a part of a system of woods and forests, coppices and spinneys which span hills and valleys and more importantly present obstacles to troop movements, funnel them in certain directions and block lines of sight.

Landscape matters!

Moreover Landscapes vary between theatres of war, Bavaria is different from Italy and from Prussia, the topography varies, the vegetation is different, there are cultural differences in the way that roads, villages and other features of human habitation are laid out and constructed. Drive through any part of Europe and you can see the difference; Normandy is distinctive and different from Flanders and you can tell where you are just by the look of it. Now try doing that to the average wargames tabletop? If you are lucky the buildings might have a faintly Germanic look, but often they are the wrong construction for both the period and the region they are supposed to depict. Yet the wargamer will proudly tell you that the 74th Regiment of Line, which his models depict, have silver buttons and not the standard issue brass ones. Except they are marching through a housing estate in Chipping Sodbury circa 1920 and not the Silesian peasant village of 1756 that he images is on his tabletop. The hyper-realism of uniforms and rule-sets distracts the wargamer from depicting the battleground as a whole, with the exception of the post 1900 gamers who really do spend time on the look of their terrain, because it is recognised that terrain affects their battles to a marked degree.

Wargames Using Maps as Landscape

My search for the using the concept of Landscape in wargaming in the period 1618-1815 came from trudging round staff rides and battlefield tours with Christopher Duffy and John Buckley. The often muddy fields bore little relation either to my experience of wargames nor the neat little diagrams showing the course of the action. The only thing that came close to expressing the complexity of the situation on the ground were topographic maps, often small scale ones of 1; 10,000 and not the 1; 50,000 Ordnance Survey ones that you usually see.

The inspiration for using maps as tabletop terrain for the Age of Battles project originally came from a series of articles written by military historian Paddy Griffith in Wargamers Newsletter of 1975 and then found more modern expression from the Forward March blog How to Create 3D Maps for Games and How to make my map panels where the author uses painted sheets to create terrain and to create realistic landscapes.

Ferraris map of Louvain in Belgium in 1770

I decided to take this basic idea and to use it with historic maps, starting with the excellent Ferraris maps from 1770 of Belgium (scale 1; 11,530) Full size Ferraris maps of Belgium which provided me with both a wide variety of terrain types from flat coastal beaches, right through to hilly regions but also to a wide array of fortress towns, and all in the pre-industrial age. In addition the maps covered a number of historic battlefields including Louvain, Ramillies, Ligny and Waterloo.

Depending on the period and the size of the battle to be recreated, I need maps in 1; 1,000, 1; 2,000, 1; 5,000 and 1; 7,500 and evolved a system for doing this for the Ferraris maps. The technique was based on the fact that my printer (a Canon G5000 series) would print out an A4 or A2 image as a poster of 16 A4 sheets, in effect giving me an A0 poster. Getting the printer settings to be consistent was a bit of a chore and the second problem was that the printed sheets included a generous border to allow them to be glued together. This meant that the final map (or if you like image,) was smaller than A0 and therefore shrunk down to fit into the printed area. By trial and error, I evolved a method to correct this.

A map depicted in Englis miles and Military Steps

Checking the correct scale of historic maps is relatively easy, using either geographic features or long standing human structures, such as churches, as measuing points and then checking the actual distance on Google Maps. Some maps come with a scale and this can be used too, although care needs to be taken as they often use ancient measurements such as Toise or use variants of well known ones such as a Mile or League. So i always compare this measure to an actual distance on the ground.

Recently I have been reading this wargames blog on creating maps for Kreigspiel games Ed M's Wargames Meanderings : Map Room: Period Battle Maps For KS/BBB Gaming where Ed uses old historic maps and colours them using chalk pastels. He takes old maps, removes the annotations and then colours them. This inspired me to have another look at my map scaling methodology to see if I could get a more accurate scale A0 poster. Also I did a test print of a Victorian map of the Battle of Albuera, colouring it using chalks and it came out very well. Quite different from the Ferraris maps and a step away from a physical representation of terrain but nonetheless a useful wargames tabletop.

Scaling maps

The first issue to address was the correction of the border issue, so I measured the border of a page printed by my printer both crossways and up and down. 14mm seemed to fit the bill and so 8 of these borders (two for each A4 sheet in both directions) meant that my A0 poster (1189 x 841 mm) would actually have an image of 1,068 x 736 mm. If resized to A2 (the largest image that the printer can handle,) then the printer will produce a 4 x 4 A4 sheet of A0 size and hopefully, not have to resize it to fit on the available printed area. So that is what we are aiming to produce.

Now that we know the ‘area’ that we have available, we can work out what this means in terms of scale. So, if my rules need 1:2,000 ground scale, that means 1 mm on the table top will represent 2 meters (2,000 mm) in real-life. :1,5,000 means 1 mm equals 5 meters and so on. Given the rules I use are pretty fixed, this means that I can produce a table of the rules, their scales and what my reduced size A0 represents.

What an reduced size A0 sheet represents on the ground for various rules and scales

Now it is an easy matter to capture an A0 sized area of terrain off any old map. Simply measure a box of the requesite area corresponding to the scale you want. So for Horse, Foot and Guns measure out 8 km by 5.5 km on the old map. Cut out the image and resize it to 1068 x 736 mm and you have rescaled it to 1:7,500.

Creating Tabletop Maps

Doing this in practice poses two problems, firstly how to measure 8 km on an old map and secondly how does an A0 sheet relate to our wargames table? To address these problems, I use Fastone Image Viewer which allows me to crop and save multiple images from one image.

Determining how many pixels equal 1 km

To measure the distance on the map, I start with the scale given on the map and see how many pixels equal 1 mile or Toise or whatever measurement is used and then convert that to kilometers. There are helpful websites to tell you about ancient measurement systems. Then I check this calculation by measuring known points on the map and comparing it on Google Maps. In both cases, I simply select the ‘Crop’ tool and select the scale or points on the map and the tool shows me the number of pixels. This does limit me to north-south or east-west measurements but I can find something to measure close to those directions.

Cropping the map into scaled A0 rectangles

Once I know how many pixels equal I km, I can then use the ‘Crop’ tool to create a box sized to my A0 area, position it, cut it out from the map and save it. For example, if 25 pixels = 1 km, and I need a 1:7,500 map, then I would cut out a box (8.01 x 25 = 200 px and 5.520 x 25 = 138 px) using the ‘Crop to Clipboard’ feature and paste the new image into another image programme such as MS Paint. Doing it this way, allows me to move my selected area and then cut out another A0 box, allowing for a small overlap.

Relationship between Tabletop and Printed Sheets

The reason for doing it this way is that I am going to fill my entire wargames tabletop with a mosaic of A0 sheets. On Club days we use boards 8’ by 4’ so I want a number of A0 sheets to fill the 4’ width and as much of the 8’ length as I think useful. For the recent Waterloo and Wavre 1815 game, I filled the entire surface with maps, while a smaller battle like Lutzen 1634 might only need 4’ of length. 4’ is 1,219 mm so my A0 map at 1068 mm is too small, so I will need part of another A0 sheet (probably a single row of A4 sheets from along the bottom). The 4’ to 8’ length will require 3 and a bit A0 sheets to cover the entire 8’. So what I end up with is a mosaic, something like this, 6 A0 sheets to cover the almost the entire 8 x 4’ board. To cover 4’ length I usually use 4 A0 sheets.

Once I have captured 4 or 6 A0 sheets covering the area that I want, the next step is to use Ed M’s technique to create printable 4 to 6 PDF documents (each being an A0 sheet of 16 A4 sheets) and remove the annotations if needed. Personally, in some cases I like to leave them it but often its better to do the work and remove them. Then it is simply a case of printing off the sheets onto heavy weight paper (250 gsm is a good start) often with a bit of a nap to it. Cut off some of the borders, stick them together with glue or double sided tape and colour the maps as required as described by Ed M. I found that this technique was superior to my earlier one of just printing direct from an image and using the printer scaling, as the PDF captures the settings and ‘fixes’ the maps which avoids printing problems later. It is straight forward where only part of an A0 sheet is required to select pages 13-16 and just print off the bottom row.

Once the work is completed, you will have a vast wargames tabeltop, with a huge amount of features and information on it already to which you can add 3D models of woods, forests, houses, hedges, walls and other items to bring it to life. Want to emphasise an important hill, then simply print a copy of that particular A4 page from your PDF document, cut out the hill shape and mount it on thick card to create an elevation.

Sources of old maps

An excellent source for such maps is David Rumsey Historical Map Collection which has large images of many atlases and battle plans which are free to download and are sufficently large file sizes to enlarge to wargames ground scales. The collection includes:

Alison: History of Europe which provides over 100 maps for the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic War and search for Alison)

Franz Kausler and Joseph Woerl ‘Die Kriege von 1792 bis 1815’ with two volumes of battlefield maps and campaign plans

The Munich Digital Library is another source of larger file size images and contains

Friedrich Rudolf von Rothenburg: Schlachten-Atlas (French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars) this copy is missing many of the battle plans so I shall have to find another source.

The Ferraris maps of Belgium can be found here: Full size Ferraris maps of Belgium with levels corrected - Wikimedia Commons at 1:11,530 and dating from 1770 they are an incredible resource of high quality maps from the pre-industrial age.

The State Library of Saxony has these excellent sheets of Saxony from the end of the C18th Meilenblätter von Sachsen, 1:12,000, 1780-1806 with other series at 1:8,000, etc.

The British Royal Collection has a superb collection of battlefield and camp maps dating from the time of George III, so from 1740s right through to 1815.

Listings of old maps can be found here:

Maps – Kriegsspiel blog provides Kreigsspiel maps for sale which are ideal for general terrain, especially the Metz series and at 1:8,000 already scales for wargames use. The Blog lists other sources of maps too such as Deutsche Fotothek, an American Civil War map maker (Hal Jespersen's Cartography Services), the British Library (links all broken and the maps are only available as paper ones in person, Kriegsspiel maps in the British library – Kriegsspiel) and American Civil War maps at the Library of Congress (Civil War Maps, Available Online | Library of Congress.)

Napoleon Online - Maps of the Wars 1792-1815 (too small scale to be useful but has a good bibliography)